Badge of Honour

The Pearson Rose has been our guarantee of provenance for more than 160 years. Will Pearson looks back at how this humble bloom became a big noise.

What connects Pearson to lovelorn ancient queens, brutal wars, a leading perfume, and the most successful drama series ever? The answer is, of course, the humble rose.

What we think of as a quintessentially English bloom has been symbolic, around the world, since Antiquity. Cleopatra allegedly adorned her bed with rose petals to demonstrate her love for Mark Antony and presumably — there might have been a touch of Shakespearean license when he immortalised their love on stage — to mask the smell of asses’ milk. (Whoever thought it a good idea to milk a donkey?)

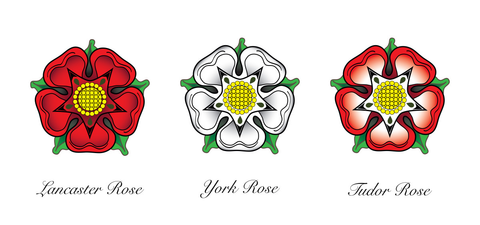

At home, roses are synonymous with the Wars of the Roses, a period of notably uncivil strife that spanned approximately three decades. Fought between rival branches of the Plantagenets, both of whom claimed descent from Edward III, the House of Lancaster was symbolised by the red rose, the House of York by a white rose. Historians continue to debate the true duration of the wars. We know they began on 22nd May 1455, at the first battle of St Albans, where Richard of York defeated the Lancastrian king, Henry VI, son of Henry V, once-more-unto-the-breach and all that. Richard subsequently imprisoned him in the Tower of London, where he was kept alive to prevent supporters rallying to his son. Lancastrian power then switched to his wife, Margaret of Anjou, who was desperate for their son, also Henry, to ascend the throne.

A conflict exacerbated by powerful aristocrats, many of whom funded private armies, those 30-odd years saw slaughter on an epic scale. At the Battle of Towton, for example, on 29th March 1461, more than 50,000 soldiers took the field. A favourable wind that day gave Yorkist longbowmen a distinct advantage; such an advantage that as many as 28,000 men were killed, in what remains the largest battle fought on English soil. (Medieval engagements were typically short, yet the Battle of Towton lasted 10 hours.) There were acts of personal sadism; Margaret’s party piece, for example, having led the Lancastrian charge on numerous occasions, was to allow her son to choose the punishment for captured enemies. Henry, just seven years old, frequently chose decapitation.

And there were also acts of extraordinary bravery. Andrew Trollope, another key figure, fought the second battle of St. Albans, on 2nd February 1461, with one foot staked to the ground — a pike used to defend against cavalry had inadvertently been driven through his foot. The wars ended on 16th June 1487, when the House of Tudor, Lancastrians led by Henry VII, defeated the House of York at the Battle of Stoke Field. Much of what we believe about the role of roses in the wars is, again, due to Shakespearean license.

The House of York used numerous symbols on their standards; and the red rose was adopted by Lancaster as late as the 1480s, the wars’ closing years. The deeply personal rivalries and internecine nature of the Wars of the Roses also proved a major inspiration for George RR Martin’s Game of Thrones, the most successful TV show in history.

Elsewhere in literature, The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco, is a medieval murder-mystery that employs highbrow literary theory and has sold more than 50million copies since it was translated from the Italian, in 1983. The English Roses, on the other hand, is a not-quite-so-well received children’s picture book, penned by Madonna. One critic, the popular children’s author Francesca Simon, pointed out in an sniffy interview with The Guardian newspaper, that people who purchased the Madonna title on Amazon also bought David Beckham’s autobiography, Trinny and Susannah’s What Not to Wear and the Madonna Encyclopedia. Meow.

It’s not only in the world of dragon-dancing drama that roses have proved a multi-billion-pound success story. ‘Floriculture’, the cultivation of flowers for sale, began in 19th century England, around the time Tom Pearson, our founder, was wandering the lanes of rural Surrey. In fact, what Tom reported to be meadows of wild roses may well have been blooms bound for market. Today, the global industry in cut flowers is worth in excess of $100bn, of which Britain contributes around $2bn. By far the majority of blooms we enjoy in the UK, around 90 per cent, are imported. The largest grower and exporter of roses in the world is Ecuador, which exports well north of $800m of roses annually. Purists, meanwhile, like to buy British-reared blooms, citing lower air miles and accepting the imperfections that come with less-reliable growing conditions.

Perhaps the ultimate rose purists reside in the perfume industry. Chanel №5, for instance, uses only those roses cultivated in a secret valley, near the town of Pégomas, in the French Alps. Abundant in petals, the varietal is known as rosa centifolia, the ‘hundred-petal’ rose. The seasonal harvest, of around 50 acres, must necessarily take place in just two weeks. That’s 37 tons, all picked by hand. A kilogramme of petals requires between three hundred and 500 blooms. A 30ml bottle of Chanel №5 Parfum requires twelve Pégomas roses, plus an additional 1,000 jasmine flowers. At an approximate retail price of £240, that works out at roughly 48p per bloom. Value for money? Hard to know; at the time of publication, the leading British supermarket, Sainsbury’s, was offering 10 roses, intensively reared in Uganda, for £2.50. A 12-bloom bouquet from an online florist, however, would set you back at least £25.

The Pearson Rose has been Pearson’s guarantee of quality for more than 160 years.

To find out a little more read Ride The Rose >